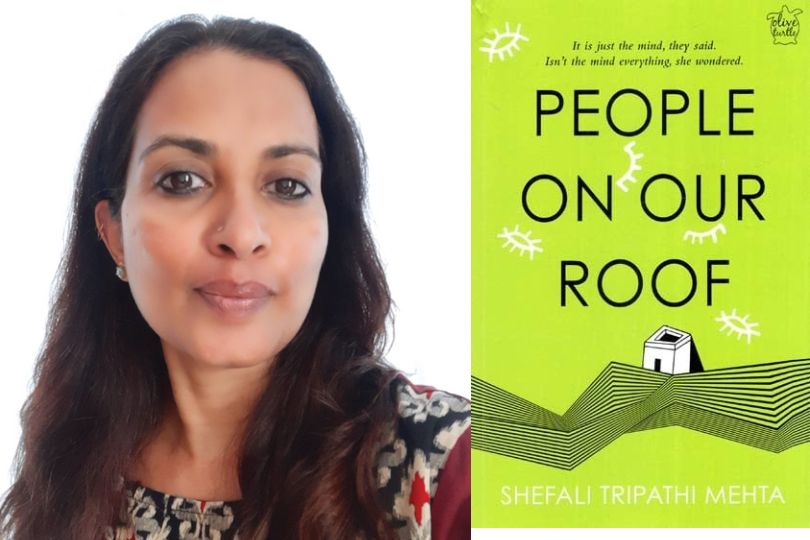

Interview with Shefali Tripathi Mehta, Author of “People On Our Roof” & More

Interview with Shefali Tripathi Mehta, author of "People on Our Roof," on writing about mental health, social issues, and disability awareness. Discover her insights on frontlist.on May 23, 2024

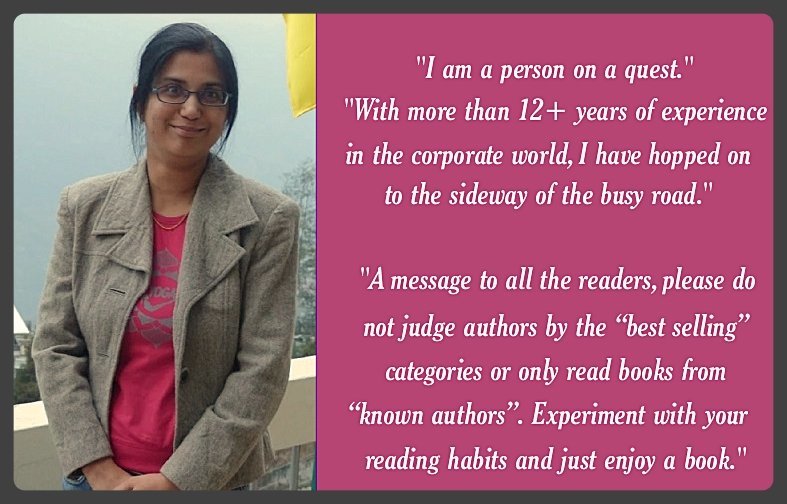

Shefali Tripathi Mehta’s most recent book is Ek Koshish: The Story of Arushi (2019). This is her fifth book and the second work of fiction after Stuck Like Lint (2017). She has published short stories and poems in anthologies and online. She writes on disability awareness, social issues, travel and parenting. For close to ten years, Shefali wrote the cover story for the Sunday supplement of the Deccan Herald. She lives in Bangalore and works at the Azim Premji University. Shefali volunteers with the disability organization, Arushi, and curates Gond art to support tribal artists.

Frontlist: Your writing frequently delves into social and mental health issues. Could you share where you draw inspiration from and the driving force behind exploring these themes in your work?

Shefali: You are right. I have always been fascinated with how the human mind works, mainly in terms of relationships. Though we call most humans who behave in expected ways ‘neuro-typicals’ in reality, there are differences even among this large majority. Why does society not censure those who have uncontrolled rage, vengeance, rivalry and aggression that impacts others? We have no problem mixing with a person who abuses their family members, but we will not include someone with cerebral palsy who is gentle and kind and harms no one. I have been deeply distressed by the exclusion of people who do not fit into our ‘mainstream’ norms for reasons that are beyond their control. This is something I have tried to bring across subtly in my stories.

I am a volunteer with an organization that works with people with disabilities, and the most important part of our work is not just to empower people with physical and cognitive disabilities but also to create awareness among others about them.

On the one side is an individual’s inability to conform to societal norms and standards, say, due to autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia – both of which have been mentioned in People on Our Roof, and on the other is society’s complete, unsympathetic, even unreasonable rejection of them. A rejection that is based on myths and stereotypical mindsets. What better way to talk about this, create awareness, and hold up a mirror for us as individuals and as a society than to weave it into an engaging story?

Frontlist: How do you maintain inclusivity and respectfulness towards diverse mental health experiences and communities in your writing?

Shefali: An engrained value system steers us towards the calling of our life. But it is not enough to ‘feel’ things, the fire in the belly should make one want to do more. With respect to your specific question, I would say I had a shift in my thinking when I started to ‘educate’ myself on inclusion and respect for others.

Therefore, firstly, it requires a shift in our mindset – we don’t put all the children who wear spectacles in a separate class. There was a time when it was a taboo – young people who needed glasses were called names; girls were told that wearing spectacles could hamper their chances of getting a good groom. Look now, who cares? We normalized wearing spectacles. This is the attitude we have to adopt towards all types of diversity. We have to mix more – have more children with disabilities study in regular schools with other children, not just for their benefit, it enriches the lives of other children too.

When mindsets change, it will reflect in our language and actions. Consciously, we need to use ‘people-first’ language – not ‘an autistic person’ but a ‘person with autism.’ How do we behave when we are in the company of a person with a disability – are we overprotective or awkward? We have to learn how to engage with them – if you’re handing a glass of water to a person who is blind, say to them, here is a glass of water. Most people are not deliberately indifferent or rude to people with disabilities; they just don’t know how to be around them. It all comes down to opening ourselves to accepting and embracing diversity.

Frontlist: Your work reflects a deep understanding of social issues. How do you weave these broader societal concerns into your narratives while maintaining a focus on individual mental health journeys?

Shefali: It is individuals that make a society, so it’s difficult to keep the two apart in writing as in reality. In People on Our Roof, the reader is, on the one hand, taken into the lives of these four people living as a family – their daily travails because of the mental health conditions of two of them – it is a lot for a family to live with but added to this is the total absence of outside support, the indifference, and a sort of ostracization by the community.

I have not dwelt too much on individual mental health journeys but on the impact of these on the life of the caregiver. The caregiver is a part of the social set-up in which, here, the protagonist, Naina, has to live, work, earn, meet people, respond to their questions, fall in love, be rejected, reject those who judge her by her circumstances, and so on; and at the same time, not have any support from the outside world. At times, when she begins to second guess her own mental health, it is because people around her have driven this notion into her.

Frontlist: How do you balance the emotional toll of delving into mental health themes in your writing with prioritizing self-care and maintaining your own mental well-being? Has writing about these topics served as a form of personal catharsis for you?

Shefali: Personally, I must confess that I would feel very low at times after writing parts. My main concern while writing this novel was to maintain a balance so that the story did not become too sad or difficult to read or act as a trigger for many with low pain thresholds. My story had to be about courage and redemption so that at no point does it get depressing. It has aspects of deep love, care, humor and strength. Life is a mixed bag for each one of us; our challenges may be different, but our strength to persevere and live the life we want to and at the same time give back to society is the notion that resonates through this story as Naina not only builds a wonderful, successful and happy family life for her family, but she also supports others. She becomes this person only because she embraces her life with all its challenges. I have wept with Naina, and I have felt her distress, but I have also experienced her joys, her big and small wins, her strength, grit and success.

Frontlist: Amidst your professional commitments and daily responsibilities, how do you carve out time to balance your writing and creative endeavors, particularly after a demanding work or study day?

Shefali: I’m not a one-thousand-words-a -day writer. I write when the compulsion to do so is strong and it helps me balance a demanding day-job and other commitments. I let the story or ideas simmer in my head long before I am ready to type it out. It helps me put out my best work. But I do envy writers who can write in a more disciplined way.

Frontlist: What advice would you give to aspiring writers who want to tackle mental health topics in their work, focusing on creating joy in reading while addressing complex issues?

Shefali: Yes, this is tricky. One thing to remember in writing a story of this nature is that even as one is writing about difficult things, one eye should be on hope. I think it also has a lot to do with the writer’s personality – if, as a person, one is able to see life in its entirety with all its joys and sorrows as part of a whole – one will be able to bring the balance into their writing. There is no formula; each one must arrive at their own.

Frontlist: How do you balance the inherent joy of writing with the responsibility of captivating and engaging your readers? How does this dual purpose shape your approach to crafting narratives?

Shefali: Fortunately, these are not two different purposes for me while writing. My joy in writing comes from writing in a way that will engage readers. But self-censure must be brutal – one should not be too much in love with one’s own words. One has to keep coming back to drafts objectively and very often leave out large chunks that one may think have been written brilliantly, but are they serving a purpose in the story – will your reader read it or skip it to get to the plot – is a question we need to ask all the time.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.